The spacing effect shows that the most efficient way to learn material is to expose yourself to it at increasing intervals, instead of cramming. Spaced repetition learning uses this effect to show you flashcards at intervals optimised for knowledge retention.

This is especially good for learning languages – it’s how Duolingo decides when to show you old vocabulary to review. So why not use it for learning programming languages as well?

Gwern has written an excellent review of the spacing effect and spaced repetition learning. He proposes this heuristic for when to commit knowledge to a flashcard:

[D]on’t use spaced repetition if you need it sooner than 5 days or [knowing it by heart will save] less than 5 minutes.

It’s likely that most language features and structures are going to net you more than 5 minutes saved. Weird corner cases, little-used syntax used to impress your friends, and extremely straightforward facts about a language might not be so useful.

How it works

Skip this section if you’re already familiar with spaced repetition flashcards and want to get to the how-to.

In massed repetition (think cramming for a vocabulary test in French class), you might make a flashcard with two sides, like this:

FRONT REVERSE

[ an apple ] [ une pomme ]

You’d show one side of the card, try and recall the answer, and then flip it over to see if you got it right. Then you’d repeat a bunch more times until it “stuck”, and after your test, would probably never look at the card again. This process of active recall strengthens the memory beyond what you’d get if you just flicked through the flashcards without thinking.

Spaced repetition is a bit different: you still have to challenge yourself to recall the answer, but you then put the card away and look at it again in a few minutes. After the second review, you look at it again in a few hours – and then a couple days, and then a week, and then a month, until the next review is several years away.

Early practitioners of the learning style managed this spacing manually, but software exists that will do it automatically, and adjust the spacing depending on how difficult you find a particular card.

Some facts are also really two entries: in this case, apple : pomme and pomme : apple are separate facts. Again, spaced repetition software will treat them as separate cards.

Spaced repetition learning only requires a few minutes a day (and exponentially less as the repetitions get further and further apart!), but it does require consistency. If you make it a habit, though, a couple of minutes per fact and you can retain it literally for years.

Making cards

I’m brushing up on my Rust. Here’s how I made flashcards to help remember what I’d done:

- Download Anki. I’ve already been using this for a while; there’s also an iOS app (paid) and an Android app (free).

- Install the Power Format Pack, which gives you Markdown formatting.

- Create a new deck (or use the default one, and use tags to subdivide your cards).

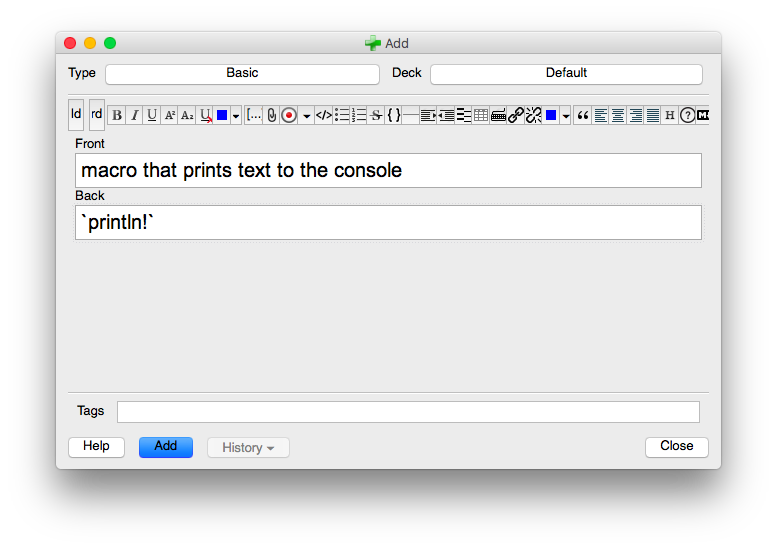

- Make your first card! Here’s a simple example:

Make sure to hit the Markdown render button (the rightmost button in the format panel) to render the card (⌘⇧0 on a Mac), and then save the card (⌘↵).

Make sure to hit the Markdown render button (the rightmost button in the format panel) to render the card (⌘⇧0 on a Mac), and then save the card (⌘↵).

The ‘Basic’ card type is fine. You can also use ‘Basic (and reversed card)’ if you want Anki to generate a reverse card (in this case, one that asks println! and expects you to answer “macro that prints text to the console”).

Reviewing

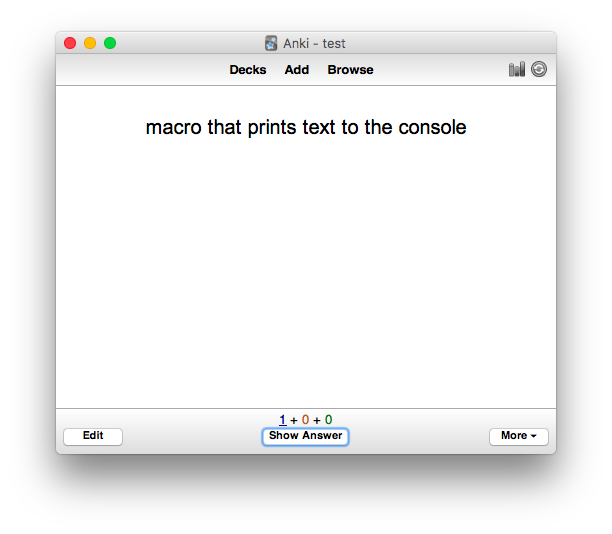

Okay - you’ve added some cards, so now it’s time to study them. Click on your deck, then on “Study Now”.

Try to recall the answer, then hit space to reveal:

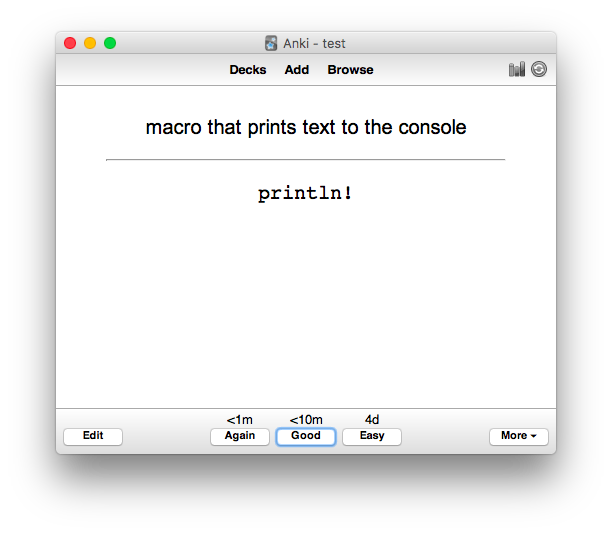

Now grade your response using the buttons provided (they’re also mapped to the number keys for speed), or hit space to accept the default.

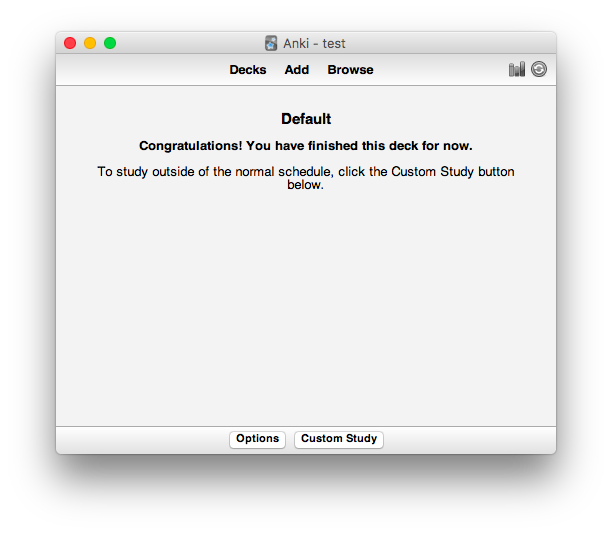

Sweet, we’re done for today. Come back tomorrow and do the same again. If you’ve added lots of cards, Anki will drip-feed them to you over the course of a few days.

The long term

As you may have guessed, this is a long-term, incremental (but very efficient) approach to learning. Instead of cramming and then forgetting, the machine will decide which facts are on the cusp of slipping out of your brain, and challenge you to remember them, greatly strengthening the memory.

But it’s a commitment that you need to keep up, ideally for a few months at least. Per card, you’ll only ever spend a couple minutes total reviewing it (hence Gwern’s recommendation not to bother with facts that you’ll spend less than 5 minutes just looking up). And you’ll retain near-perfect knowledge of them for decades.

(I’ve certainly not been perfect – there have been times when I’ve done my Anki reviews daily, and sometimes months go by without me looking at it.)

I’ve used this process when learning Ruby, Go, bash, BOSH CLI commands, Cloud Foundry concepts and various other (spoken) languages. Give it a try.